Sara Kåll-Fröjdö

The concept of inventory, collecting and revitalization of cultural traditions has slowly given place to a strategy where safeguarding, cherishing, and promoting of the diversity of intangible cultural heritage is important. In this view intangible cultural heritage is traditional, contemporary, and living at the same time. It is inclusive, representative, and community-based with a bottom-up approach.

Intangible cultural heritage

Intangible cultural heritage are cultural expressions which are born directly by human knowledge and skills, including oral traditions and expressions, performing arts, social practices, rituals and festive events, knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe as well as traditional craftmanship. This heritage is passed on in the form of skills, abilities and knowledge and it is constantly changing because living heritage is adapted to varying circumstances and times, by the communities, groups and individuals that practice the intangible cultural heritage. (UNESCO 2022b.) Intangible cultural heritage depends on performance, as the practitioners act out their knowledge through for example song, handicraft, or storytelling (Björkholm 2011).

Intangible cultural heritage is present in people’s everyday lives, in all forms of human activity.

Johanna Björkholm concludes in her dissertation on intangible cultural heritage as a concept and process with traditional music as an example, that performativity appears crucial to an understanding of cultural heritage – when a sufficient number of people speak and act as if a cultural component has a special status, it will also be perceived as cultural heritage (Björkholm 2011).

The Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage

The UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage was drafted in 2003. As of 2022, 178 states have ratified the Convention. (UNESCO 2022a.) As a part of the implementation of the Convention, each state will make an inventory of intangible heritage. The purpose is to raise awareness of the importance of intangible cultural heritage and share best practices.

Finland ratified the Convention in May 2013. Because the UNESCO framework emphasizes a bottom-up approach and that communities should play a significant role in the identification and definition of intangible cultural heritage it is suggested that the national implementations is carried out as a networking activity, with participation of communities and stakeholder groups. The Finnish Heritage Agency opened a Wiki-inventory for Living Heritage to enable communities and groups to present their own intangible cultural heritage. Content is produced by communities and stakeholder groups and the Finnish Heritage Agency is moderating and upholding the site. (Museovirasto 2022.)

All the other Nordic countries has also ratified the Convention: Iceland in 2005, Norway in 2007, Denmark in 2009 and Sweden in 2011.

The Representative List of the Intangible Cultural of Humanity is a list by UNESCO, made up of heritage elements from around the world that help demonstrate the diversity of this heritage and raise awareness about its importance. It is a different list than the more widely known World Heritage List. The Sauna culture in Finland was inscribed in the Representative List in 2020 and the Kaustinen fiddle playing and related practices and expressions in 2021. In a Nordic context, the Nordic clinker boat traditions were inscribed in 2021. The clinker boat tradition was nominated by Denmark (including Faroe Islands), Finland (including Åland), Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. These heritage elements are inscribed in the list among elements such as for example Chakkirako dance in Japan, the traditional system of Corongo’s water judges in Peru, Majlis – a cultural and social spaces in Oman, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates, the Mbende Jerusarema dance in Zimbabwe and Ommegang of Brussels, an annual historical procession and popular festival in Belgium (UNESCO 2022b.)

Bottom-up Safeguarding Practices and the changing role of archives?

Safeguarding means ensuring the viability of intangible cultural heritage – its continued practice and transmission. Documentation and filing in archives have been associated with safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage, but as Johanna Björkholm (2011) points out in her dissertation on intangible cultural heritage as a concept and process, forms of safeguarding that support performance and transmission are called for.

The role of archives has been changing over the years. Outi Valo (2022) has in her dissertation disseminated how traditional music has been documented and collected reflecting ideologies, from the beginning of the 18th Century to the 1970ies, focusing on the work of Erkki Ala-Könni in Finland. Valo (2022) points out how national-building and a national gaze guided data collection practices after the 2nd World War in Finland and this affected archive collections, folk music research, the music policy of the Finnish Broadcasting Company and folk music events. The interests of the collections gave an image of an apparent coherent population when, in reality, the population was much more heterogeneous than the collections might imply. In the 1960s the view of both Ala-Könni and in general in Finland started to change, driven by trends in sociology, f.ex. acknowledging conflicts. (Valo 2022.) There was still collected proportionally seen little material related to women, indigenous people and minorities and as Valo (2022) states the attitudes represented would not be understood as culturally sensitive from today’s point of view. The question to be asked is what is not found in archives and how is the selection on what to archive made and by whom.

A historical concept of inventory, collecting and revitalization of cultural traditions, skills and (musical) languages has overall developed into a different approach: knowing, doing, and passing it on, an approach where safeguarding, cherishing, and promoting the diversity of intangible cultural heritage is important. Intangible cultural heritage is traditional, contemporary, and living at the same time. It is inclusive, representative, and communitybased. (UNESCO 2018.)

Intangible cultural heritage is constantly recreated by its bearers, a manifest of a certain practice might be slightly different every time. The heritage is transmitted from person to person and from generation to generation. Mostly this depends on orality, not on, for example, written texts. A threat to transmission is reduced intergenerational contacts, caused by for example migration and urbanization. (UNESCO 2022b.)

Who are then the communities or groups referred to? The UNESCO convention mentions communities and groups in a non-specific way, with an open character not necessarily linked to specific territories. The states that have ratified the convention have committed to taking measures to involve the widest possible participation of communities, groups and individuals that create, maintain and transmit intangible cultural heritage and involve these in the management. There are also several accredited NGO’s worldwide that provide advisory functions to the Committee. The Finnish Folkmusic Institute, the Norwegian Center for Traditional Music and Dance and the Storytelling Network of Kronoberg are examples of Nordic accredited NGO’s. (UNESCO 2022b.)

A good example of a Safeguarding Practice by a community is the so called Näppäripedagogiikka or the Näppäri method, a way of teaching music to children and youth focusing on the traditional fiddle music in Kaustinen and surrounding areas, but also other traditional music. The central thought is that children of different ages and of different skill level play and sing traditional music together, that the practicing of music is free for all to join without entrance or skill level tests and build on the joy of playing music together. The thought is also that playing music should be an integral and normal part of everyday life. (Järvelä 2014; Safeguarding Practices 2022.)

Social Sustainable Development and Inclusiveness

There are a several international strategies and treaties that emphasize the importance of culture in a context of sustainable development.

For example, the Sustainable Development Goal 11.4 in the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development states that we should strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage (United Nations 2022). The goals of the 2030 Agenda are to be met by 2030 and apply to all countries of the world.

The Faro Convention by the Council of Europe is in turn a multilateral treaty that emphasizes the important aspects of cultural heritage as this relate to human rights and democracy. Cultural heritage is seen as important because of the meanings and uses that people attach to them and the values they represent (Council of Europe 2022).

In a Nordic context, it is interesting to note that culture in general and intangible cultural heritage specifically as well as social sustainable development are highlighted in the strategic environmental assessment and socio-economic analysis of the Interreg Aurora programme document. Interreg Aurora is the new programme for cross-border cooperation in northern Finland, Sweden, Norway and Sápmi, covering the years 2021-2027. The background analysis for the program states that culture has an integral value to human beings and that it is important to support opportunities for societal wellbeing, whether they are provided by leisure time interest groups or produced professionally. Culture is seen as an important driving force to strengthen people’s creativity and create local and regional cohesion, and the program states that it is important to create preconditions for the development of future common cultural heritage. Further on, co-creating development processes are viewed as processes that create a sense of togetherness, which fosters social inclusion. Intangible cultural heritage is also seen as a force that promotes resilient societies: practicing traditional knowledge together creates bonds and understanding over generations. (The Interreg Aurora Programme Document 2022.)

When talking about social sustainable development in general, public awareness, equity, participation, and social cohesion (the extent of connectedness and solidarity among groups in society) can be thought of as key concepts (Murphy 2012). In the field of Intangible Cultural Heritage and traditional music, questions have to be asked on whom not to exclude, and which communities are missing from f.ex. archived material. The Roma communities are often left out (Engman 2022) and immigrants and refugees bringing their own immaterial cultural heritage with them is not to be seen as a threat (Björkholm 2022). Intangible cultural heritage is beyond national borders, it has historically been and still is constantly alive and changing. As of today, more than 100 million people have been forced to flee war, conflicts and persecution. This is a major challenge to the transmission of cultural heritage for communities, as communities, families, and music ensembles are separated from each other and spread out globally (Ellinghaus, 2022).

The ICH North-project as a potential way to tackle to the “wicked problem” of endangered musical heritage

Catherine Grant (2014) discusses in an article the issue of musical heritage at risk, pointing out that while musical traditions nowadays tend to be framed in more pragmatical ways with the view that music genres ebb and flow over time, global circumstances including fast social and technological change does put a large pressure on many local communities worldwide. In the end the transmission and practice of traditional music in these communities might be significantly weakened, against the will of the communities themselves. She argues that endangered musical heritage could be seen as a so called “wicked problem”, that is, a problem that is complex, ill-defined and resist solution, typically social or cultural in nature. (Grant 2014.)

A wicked problem is often dependent on other problems, there is a large diversity of stakeholders and opinions and contradictory or incomplete information. Grant (2014) also states that since there is no clearly formulated problem in a wicked problem, there is also no definitive solution. When it comes to music endangerment, there will not be any definite end-point, for example that all musical heritage is kept vital in the future. There is no way of knowing when success has been reached and problem-solving will not include finding one solution. Grant (2014) also argues that solutions cannot be right or wrong, only better or worse, good enough or not good enough. All wicked problems are unique, while they might share similarities, as f.ex. language and music endangerment. The varied factors that cause a wicked problem are changing and evolving alongside the efforts to solve it. (Grant 2014.)

Grant (2014) states that there might be solutions to music endangerment that are not yet perceived, and it remains to be seen if actions taken so far will be considered good judgement in the future. She also points out that the wickedness of the problem is no excuse for lack of action or delayed action – action is urgent. Even if solutions are hard to identify, policy planning and action can mitigate the negative effects of wicked problems. A rational and scientific approach to solve the problem of music endangerment would not work because a linear course and overarching analysis, or “taming” the problem, would not be efficient since the problem is so complex. (Grant 2014.)

Social innovation is considered a relevant concept to tackle societal challenges and needs in rural areas and to promote smart, inclusive, and sustainable growth. A strategy to safeguard musical heritage that engages all stakeholders, who work together to formulate the best possible solution for all those involved has the benefit of allowing active participation of all those who may be affected. The combination of a collaborative strategy and interdisciplinary knowledge, engaging different stakeholders and dealing with a wicked problem as a social process could be a good approach. (Grant 2014.)

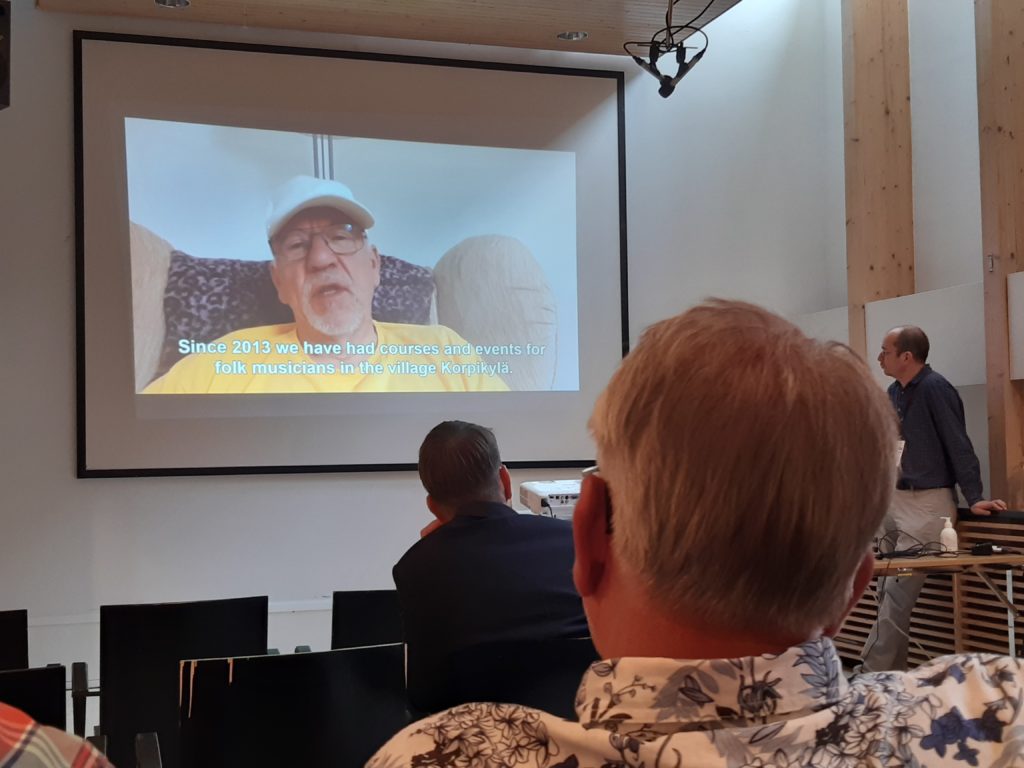

The Interreg Nord-funded project ICH North – passing on our musical heritage has during 2021 and 2022 been dealing with networking, collaborating, and planning actions to promote the transmission of intangible cultural heritage in northern Finland, Sweden, and Norway as well as Sápmi. During the project, a three-year main project was planned and an application submitted to Interreg Aurora.

The new project with the same name focuses on enhancing the role of intangible cultural heritage in the form of musical heritage in the Aurora area. It will promote cross-border cooperation related to musical ICH and enhance the role of musical communities in the area, building bridges between musical institutions, educational institutions, and heritage communities. The project is community-based in accordance with the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage and will use co-creation between communities and institutions with a bottom-up approach.

The actions planned have quite different approaches. The actions include a Massive Open Online Course on ICH in the North, open for a global audience. The actions also include an entrepreneurial approach with f.ex. tandem meetings for musicians and entrepreneurs and cultural innovation think tank events for musicians, music students, music communities and entrepreneurs. There will also be a focus on educational material on ICH, targeting adults that work within non-formal education, music organizations, civil organizations, study circles, and adults with potential interest in leadership in musical heritage communities. Educational workshops and inspirational meetings and webinars with physical nodes will bring together representatives of these groups. A digital map of musical communities practicing and transmitting their musical heritage in the programme area will be produced, co-created with the communities.

Last but not least, a joint strategy for community involvement in safeguarding musical heritage for archives in the programme will be developed, involving communities in the mapping of needs and opinions as well as elaboration of the strategy and the road map ahead. Should the project get funding, it probably will not solve the wicked problem of endangerment of traditional music, but it will tackle the problem with a bottom-up collaborative and cross-border approach in a creative way, engaging a vast number of stakeholders.

The article was written during the Interreg Nord-funded project ICH North (2021-2022). The national co-financing in Finland was provided by Lapin Liitto.

References

Björkholm, J. 2022. Personal communication.

Björkholm, J. 2011. Immateriellt kulturarv som begrepp och process: Folkloristiska perspektiv på kulturarv i Finlands svenskbygder med folkmusik som exempel. Åbo: Åbo Akademis förlag.

Council of Europe 2022. Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (Faro Convention, 2005). Webpage. Available: https://www.coe.int/en/web/culture-and-heritage/faro-convention Accessed 10 August 2022.

Ellinghaus, B. 2022. Keynote speech “Perspectives of folk music education to the safeguarding of ICH in context of postcolonialism and globalization in the age of wars”. Non-formal Music Education and Intangible Cultural Heritage Seminar at Kaustinen Folk Music Festival. Attended: 16.7.2022.

Engman, D. 2022 Personal communication.

Grant, C. 2014. Endangered musical heritage as a wicked problem. International Journal of Heritage Studies 21 (7): 629-641. Available: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13527258.2014.976245?journalCode=rjhs20 Accessed: 29 September 2022.

Interreg Aurora Program Document 2021. Available: https://www.interregaurora.eu/support/programme-documents/ Accessed: 27 September 2022

Järvelä, M. 2014. Näppäripedagogiikka. (Red) Antti Huntus. Kansanmusiikki-instituutti.

Murphy, K. 2012. The social pillar of sustainable development: a literature review and framework for policy analysis, Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 8:1, 15-29. Available: https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2012.11908081 Accessed: 29 September 2022.

Safeguarding practices 2022. The Näppäri Method. Web page. Available: https://safeguardingpractices.com/good-practice/the-nappari-method/ Accessed: 29 September 2022.

United Nations 2022.The Sustainable Development Agenda. Web page. Available: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/ Accessed: 27 September 2022.

UNESCO 2022a. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Available: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention Accessed 10 August 2022 Accessed: 8 August 2022.

UNESCO 2022b. Intangible Cultural Heritage. Web page. Available: https://ich.unesco.org/ Accessed: 27 September 2022.

UNESCO 2018. Knowing. Doing. Passing it on. German Nationwide Inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Digital brochure. Available: https://www.unesco.de/sites/default/files/2018-08/Broschuere_Immaterielles_Kulturgut_englisch_Ansichtsdatei.pdf Accessed: 10 August 2022.

Valo, O. 2022. Kansanmusiikin keruu ja kansallinen katse. Erkki Ala-Könnin tallennustyön toisen tasavallan Suomessa vuosina 1941-1974. Tampereen yliopiston väitöskirjat 564. Tampere: Tampereen yliopisto. Available: https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-03-2318-9. Accessed: 27 September 2022.

Museovirasto 2022. Wiki – Inventory for Living Heritage. Web page. Available: https://wiki.aineetonkulttuuriperinto.fi/ Accessed: 10 August 2022.

Banner picture: Children in Kaustinen taking part in local fiddling tradition, using the Näppärä method. Photo by Krista Järvelä / Kansanmusiikki-instituutti.

Sara Kåll-Fröjdö

RDI-expert

Centria University of Applied Sciences

Tel. +358 40 487 9634